When GATT was first formed in 1947, decisions were passed by majority vote, with each country having one vote. Major amendments required a two-thirds majority to pass and those countries that voted against them were not bound by them. From 1959, after many developing nations had joined GATT, decisions required a consensus rather than a majority vote, so as to prevent any block of nations, in particular developing nations, taking control of GATT decision-making.

When GATT was first formed in 1947, decisions were passed by majority vote, with each country having one vote. Major amendments required a two-thirds majority to pass and those countries that voted against them were not bound by them. From 1959, after many developing nations had joined GATT, decisions required a consensus rather than a majority vote, so as to prevent any block of nations, in particular developing nations, taking control of GATT decision-making.

Although the US had originally preferred some form of weighted voting where countries with larger economies had more votes, it soon recognised that this would have deterred many countries from joining GATT. As US economic power grew it saw that it could ‘influence’ voting without a formal and obvious weighting mechanism. Countries that didn’t accept the wishes of the major economic powers could lose access to International Monetary Fund (IMF) and other loans and suffer from trade sanctions.

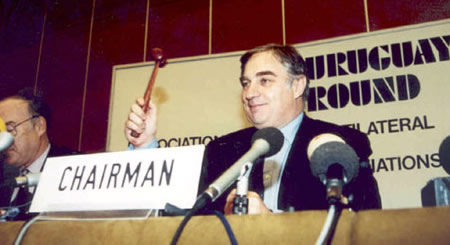

Since the end of the cold war US negotiators have been free to overtly exercise their power and they did this during the Uruguay Round when developing nations were refusing to agree to Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), Trade Related Investment Measures (TRIMS), and a General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). Developing countries had little to gain from these expansions of the free trade agenda, and much to lose. For example, because around 96 percent of all patents are held by corporations based in affluent countries, a TRIPS agreement was of no benefit to poor nations and would only cost them money and inhibit their development.

The Uruguay Round was supposed to start in the early 1980s but developing countries, particularly the Group of Ten (G10)—India, Brazil, Argentina, Cuba, Egypt, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Peru, Tanzania, and Yugoslavia—opposed the broadening of the GATT agenda to include these services, intellectual property and investment rules.

To get recalcitrant countries to submit, the US exercised its economic muscle by taking retaliatory trade actions against South Korea and Brazil. According to Michael Ryan in his Brookings Institution book, Knowledge Diplomacy, this was a bullying strategy: “The action was intended to signal that negotiations would go on one-by-one under threat of bilateral trade sanctions or they could take place within the GATT round, but negotiations would take place. The gambit worked” and the Uruguay Round got underway in 1986.

To get recalcitrant countries to submit, the US exercised its economic muscle by taking retaliatory trade actions against South Korea and Brazil. According to Michael Ryan in his Brookings Institution book, Knowledge Diplomacy, this was a bullying strategy: “The action was intended to signal that negotiations would go on one-by-one under threat of bilateral trade sanctions or they could take place within the GATT round, but negotiations would take place. The gambit worked” and the Uruguay Round got underway in 1986.

However the developing nation opposition to these issues continued throughout the negotiations as did US trade sanctions aimed at pressuring these countries to comply. Countries such as Mexico, Thailand and India suffered losses of millions of dollars during the Uruguay Round from US retaliatory trade measures because they refused to reform their intellectual property laws. The US made aid to Brazil conditional upon its cooperation on patent reforms.

Chakravarthi Raghaven, in his book Recolonization describes how the solidarity of Third World countries was broken down by pressure early in the Uruguay Round. This pressure from the US, Europe and Japan involved: offering political ‘support to beleaguered regimes against their domestic opponents or externally against neighbours’; financial pressure ‘in terms of debt negotiations’; and using their ‘vast panoply of powers to reward or punish – capacity to maintain or deny [preferential]benefits, threat of harassing actions like anti-dumping and countervailing proceedings, quotas.’

According to Richard Steinberg, Professor of Law at the University of California:

In late spring of 1990, US negotiators decided to try to build a U.S. government consensus on what some at the office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) referred to internally as ‘the power play,’ a tactic that would force the developing countries to accept the obligations of the Uruguay Round Agreements. The State Department supported the approach and, in October 1990, it was presented to EC negotiators, who agreed to back it.

The ‘power play’ was an all or nothing approach that involved incorporating the GATT agreement, the GATS, TRIPS and TRIMS and various other agreements as integral parts of the WTO, “binding on all Members”. After joining the WTO, the EC and the US would withdraw from earlier GATT commitments and be free to erect tariffs and barriers to imports from countries that did not join the WTO. This provided a powerful incentive for countries to join the WTO despite disliking many of the rules it embodied. From 1991, the unpopular agreements were integrated into all negotiating drafts.

Ryan has referred to this sort of strategy as linkage bargaining. The idea is that various issues are linked together, whether or not they have anything to do with each other, so that unpopular rules can be linked with those that opposing countries want and the whole package is agreed to. In the case of GATT, developing countries wanted better access to textile, apparel and agricultural markets but they had to agree to GATS and TRIMS and TRIPS to get that improved access.

The draft text which included all the various agreements was labelled the Dunkel draft text, after GATT Director-General Arthur Dunkel:

In India, the Dunkel draft text was labelled ‘DDT’ and thought to be just as dangerous for the health of the country as the chemical of that name. For those who had seen the Indian-designed patent system produce a flourishing pharmaceuticals sector capable of competing in global markets, DDT was very hard to swallow… Hundreds of thousands of Indian farmers protested in the streets about the patenting of seeds, but there was no negotiations in which the mass unrest could have been utilised to support a position.

The GATT secretariat, and particularly the Director-General, had control of the negotiating drafts, and after Dunkel was replaced by Peter Sutherland as Director-General, a senior US trade official told Braithwaite and Drahos that Sutherland was “conspiring with us” so that it was virtually impossible for most countries to change the texts. Countries wanting to change the text had to get consensus support to do so: “That meant effectively that only us and possibly the EU could do it”. Other nations had neither the staff resources nor the economic power to build such a consensus in a short time.