In the 1970s Edmund Pratt (pictured), CEO of Pfizer, noticed that his company was losing significant market share in developing countries ‘because our i ntellectual property rights were not being respected in these countries’. Pfizer is a transnational pharmaceutical company that set up operations in developing countries ahead of many other US pharmaceutical companies.

ntellectual property rights were not being respected in these countries’. Pfizer is a transnational pharmaceutical company that set up operations in developing countries ahead of many other US pharmaceutical companies.

Some developing countries did not have patent laws at this time because there was no economic incentive to do so. Others had patent laws but didn’t enforce them properly. Some required the patent owner to license local firms to produce the drugs if they weren’t being produced by the patent owner in their country at a reasonable price. In India and Argentina the processes and methods of manufacturing pharmaceutical drugs could be patented but not the final products. This allowed competitors to make the same drugs using different methods and sell them at a much lower price.

Some developing countries did not have patent laws at this time because there was no economic incentive to do so. Others had patent laws but didn’t enforce them properly. Some required the patent owner to license local firms to produce the drugs if they weren’t being produced by the patent owner in their country at a reasonable price. In India and Argentina the processes and methods of manufacturing pharmaceutical drugs could be patented but not the final products. This allowed competitors to make the same drugs using different methods and sell them at a much lower price.

Although Pfizer’s overall profitability did not depend on developing country markets, as they represented such a small proportion of its overall sales, the fact that generic versions of Pfizer drugs could be manufactured and sold so cheaply in these countries ‘raised embarrassing questions about the connections between patents and drug prices.’ Also Pfizer viewed these countries as potential growth markets.

Through the 1970s and early 1980s Pfizer together with IBM—another ‘globally ambitious, intellectual property-intensive’ company where Pratt had spent his early career—unsuccessfully tried to persuade government officials in the US and in developing countries that intellectual property rights needed to be protected. Nor were they successful at persuading the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO), which administered a Convention on Intellectual Properties, of the need for high standards of protection for patents. Being a UN agency, each member nation of WIPO had a single vote and the majority voted against tougher international patent protections.

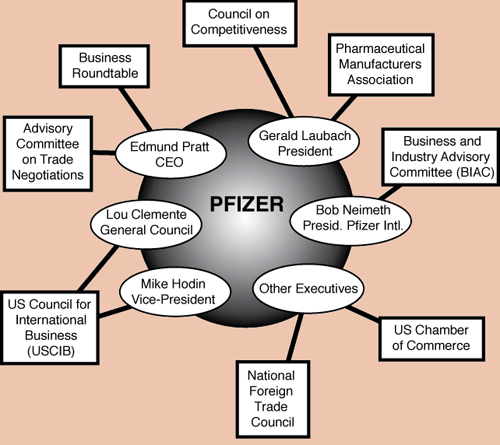

For Lou Clemente, Pfizer’s General Counsel, the ‘experience with WIPO was the last straw in our attempt to operate by persuasion’. Instead, Pfizer decided to organize and mobilize business interests to pressure governments for change. It was already a well connected company (see diagram below) and well placed to do this. For example, at this time Pratt was head of the US Business Roundtable.