The second world war, whilst restoring much confidence in the ability of business to deliver the goods, also demonstrated to many people that government controls, economic planning, and the public provision of welfare protection, could ensure a better society for all. During the war the vice chairman of General Motors had written to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) president warning:

The second world war, whilst restoring much confidence in the ability of business to deliver the goods, also demonstrated to many people that government controls, economic planning, and the public provision of welfare protection, could ensure a better society for all. During the war the vice chairman of General Motors had written to the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) president warning:

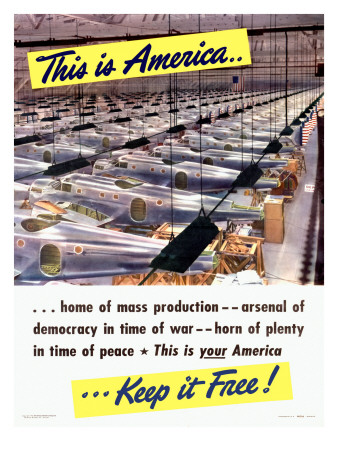

The public is profoundly conscious of the ‘miracle of production’ that industry is performing. Paradoxically enough, it is the very efficiency of our industrial system in turning out the goods required by the armed forces that endangers industry in the future through its threat to the system of free enterprise. Everyone knows that we are subject today to a high degree of governmental control, but too many may come to believe that the efficiency being displayed by industry derives from this war-time incident of centralized planning and administration, rather than the qualities inherent within industry itself.

In the immediate post war period, key business organizations were concerned about government intervention and controls on the one hand, and union activity on the other—Big Labour and Big Government. Proposals for further government intervention included price controls, a rising minimum wage, expanded unemployment insurance and tax reforms. Unions were active and in some cases demanding not just improved pay and conditions, income security and full employment through government spending, but also a say in corporate decisions in areas such as pricing and investment. They were advocating social planning and expansion of the welfare state.

The way in which business in the US used its power and resources to oppose unionism was unique in scale and comprehensiveness. In Britain unions were seen as necessary to containing radicalism and class struggle. The 1919 British Cabinet was told that ‘trade union organisation was the only thing between us and anarchy’. Following the second world war, when economic times were tough, British governments—both Labour and Conservative—expected trade unions ‘to play a major part in maintaining industrial discipline, curbing militancy, and persuading their members to reduce their demands for higher wages’. In return governments praised the role of trade unions and union representatives were incorporated into government processes through representation on committees, royal commissions, inquiries and boards of nationalized industries.

British trade union leaders tended to have narrow agendas, in terms of pay and conditions, rather than radical agendas aimed at the overthrow of the capitalist system. Whilst the same was largely true of US trade union leaders, they and the measures they were promoting were nevertheless seen as a threat to the autonomy of business and many US businessmen believed union demands were the beginning of the ‘slippery slope towards socialism’.

The Opinion Research Corporation found in 1947 that 60% of business executives said that ‘business faces a real threat in the Socialistic trend’. An even higher percentage of executives in both large and small firms (80%) agreed that more needed to be done to sell free enterprise to the American people.

Business people ‘shared a common commitment to halting the more radical features of the New Deal, such as public power, progressive taxation and pro-consumer regulation, and preserving the autonomy of corporate enterprise.’

Other problems for business, identified by the privately conducted polls, included the way that Americans were suspicious of the motives of corporate leadership; the lack of public ‘understanding’ of the role of corporations in providing America’s high living standards; the belief of workers that technological progress was not in their interest; and the ‘misinformation’ put out by ‘special interest groups that needed to be counteracted’.

Polls generally confirmed business fears that the public did not believe in the free enterprise system as wholeheartedly as business would wish. Although most people were in favour of private ownership and thought well of large corporations, a majority also thought that most businessmen did not have the good of the nation in mind when they made their decisions and therefore government oversight was necessary. Many believed that businesses made huge profits and, business leaders felt, few understood the relationship between profits and investment. Surveys showed that some seventy percent of workers believed that the government should guarantee full employment. Many workers didn’t trust their employers and were not convinced of the value of free enterprise. A substantial number of workers, in fact, supported government ownership or control of the economy.

Polls generally confirmed business fears that the public did not believe in the free enterprise system as wholeheartedly as business would wish. Although most people were in favour of private ownership and thought well of large corporations, a majority also thought that most businessmen did not have the good of the nation in mind when they made their decisions and therefore government oversight was necessary. Many believed that businesses made huge profits and, business leaders felt, few understood the relationship between profits and investment. Surveys showed that some seventy percent of workers believed that the government should guarantee full employment. Many workers didn’t trust their employers and were not convinced of the value of free enterprise. A substantial number of workers, in fact, supported government ownership or control of the economy.

Business sought to deal with these threats by selling free enterprise on the basis that ‘if you control public opinion you have the government in your hand and labor behind the eight ball.’ Public relations consultants, eager for business, promoted the need for their services. Very large sums of money were spent on lobbying, institutional advertising, philanthropy, research sponsorship and other public relations activities. But the core of their efforts was ‘economic education’, that is, the selling of free enterprise. All the major trade associations, foundations and corporations took part in this, including the US Chamber of Commerce, NAM and the Committee for Economic Development (CED).

In her history of this period, Elizabeth Fones-Wolf, explains how business groups countered the perceived trend towards socialism:

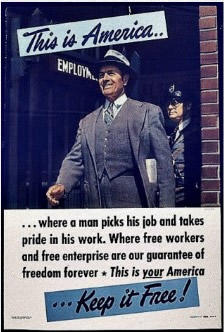

The business community... set out to build an agreement around an alternative agenda. In doing so, it sought not only to recast the political economy of post-war America but also to reshape the ideas, images, and attitudes through which Americans understood their world. Employers wanted support for the belief that economic decisions should be made in corporate boardrooms, not in legislative chambers. Prosperity was to be achieved through reliance on individual initiative and the natural harmony of workers and managers inherent in business’s interpretation of the free enterprise system.

Fones-Wolf points out that in a two pronged strategy, business organizations sought to discredit organized labour and unions by associating them with communism, which threatened individual freedom, and promote business values by appeals to patriotism and American values.

Similarly Alex Carey, in an article on ‘Managing Public Opinion: The Corporate Offensive’, argued that corporations sought ‘to identify the free-enterprise system with every cherished value, and identify interventionist governments and strong unions (the only agencies capable of checking the complete domination of society by the corporations) with tyranny, oppression and even subversion.’

Corporations, and the PR people hired by them, identified business interests with national interest and ‘the traditional American free-enterprise system with social harmony, freedom, democracy, the family, the church, and patriotism’ whilst they identified ‘all government regulation of the affairs of business, and all liberals who supported such ‘interference’, with communism and subversion.’

Henry Link, head of the polling company Psychological Corporation, argued that the promotion of free enterprise alone was not enough. What was needed to restore the legitimacy of business and prevent the interference of government was ‘a transfer in emphasis from free enterprise to the freedom of all individuals under free enterprise; from capitalism to the much broader concept: Americanism.’

What followed was ‘the most intensive ‘sales’ campaign in the history of the industry’ according to Daniel Bell, then editor of Fortune magazine. What was being sold was free market dogma, and the full weight of business resources were poured into it: ‘The apparatus itself is prodigious: 1,600 business periodicals, 577 commercial and financial digests, 2,500 advertising agencies, 500 public relations counsellors, 4,000 corporate public relations departments and more than 6,500 ‘house organs’ with a combined circulation of more than 70 million.’

Specific campaigns consumed huge resources. NAM spent over $3 million dollars on one particular campaign after the war, opposing price controls. NAM’s Director of Public Relations told how:

The NAM spent a million and a half on newspaper advertising. They sent their own speakers to make a thousand talks before women’s clubs, civic organizations and college students. A specially designed publication went to 37,000 school teachers, another one to 15,000 clergymen, another went to 35,000 farm leaders, and still another to 40,000 women’s clubs. A special clipsheet with NAM propaganda went to 7500 weekly newspapers and to 2500 columnists and editorial writers...

The Director claimed that as a result of this campaign public support for price controls dropped from 85 percent to 26 percent. President Truman strongly disapproved of NAM’s campaign and in 1948 said of it: ‘We know how the NAM organized its conspiracy against the American consumer.’

NAM also raised several million dollars for its campaign against ‘collectivism’ in 1946 and 1947 and additional funds to oppose particular pieces of legislation. However, the biggest efforts and the largest resources were spent selling the capitalist ‘free enterprise’ system generally. Of course all this advertising of the capitalist system was framed in terms of ‘public education’, a much more reputable and credible activity than advertising.

New organisations were formed to promote business values, now labelled ‘American’ values. These included such organisations as the Foundation for Economic Education (1946), the American Heritage Foundation (1947) and the Industrial Information Institute (1947) which received funding from corporations such as DuPont, Republic Steel and Ford. However at the forefront of the propaganda campaign was the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM), the Chamber of Commerce, the American Petroleum Institute and the American Iron and Steel Institute. These bodies were themselves coordinated by the Advertising Council.