by Sharon Beder

first published by Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989

Introduction

Sewers seaward

Toothless watchdog

Toxic fish

Sewer-side surfing

Public relations battle

Events of 1989

Beyond Sydney

Conclusion

Bibliography

Although the fish stories that emerged throughout the first three months of 1989 were the most spectacular, the reports of bathing water pollution were perhaps of more immediate concern to many beachgoers. That first Herald article on 7 January reported a Health Department study that showed Sydney beaches were unsatisfactory for swimming for a large proportion of the year (see chapter 4, p. 80-82) while Water Board monitoring showed the beaches were relatively unpolluted most of the time. The Herald also exposed the Surfline monitoring for what it was:

The engineered impression is that, before the day begins, Water Board experts have been on the beach conducting scientific tests on whether the beaches are safe. What is generally not known is that the test used by Surfline involves simply looking for grease, faecal matter or other rubbish and odours. The radio reports have no scientific basis. (7/1/89)

The inadequacy of faecal coliform as an indicator of water purity was revealed once again. (This inadequacy was noted in chapter 4, p. 84-85.) Dr Gary Grohmann, a virologist at Westmead Hospital, pointed out that monitoring of sea water for viruses was ‘done all the time in the US’. The Water Board subsequently began sampling bathing water at Bondi for viruses on 6 February. These samples are to be taken every three weeks at various parts of the beach and in deeper water. (Was the timing of this new study a coincidence or was the Board reacting to the publicity?)

|

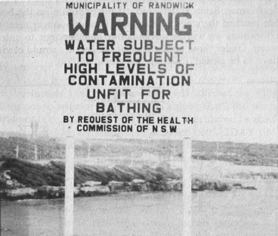

This sign is a permanent fixture at Malabar beach, yet its demise as a swimming beach because of its location next to the Maroubra outfall often goes unnoticed. Dr Ian McNeill wrote to the Herald in 1986: ‘In the early days of Sydney, Malabar was a popular picnic spot, being a safe and picturesque bay. Australia’s poet laureate, Henry Kendall, eulogised this place in his poem At Long Bay . . . The surf club folded in the early seventies due mainly to pollution. With the exit of the surf club the Water Board saw the time was right to close the beach to the public, and subsequently a sign was erected stating that swimming was not advised due to pollution of the water. What a disgrace.’ (Herald 29/12/86) |

|---|

Neale Prior of the Eastern Herald obtained some results of Health Department testing at Waverley Municipality beaches, including Bondi, and also found that they differed from Water Board results (Eastern Herald, 12/1/89). The Telegraph managed to come up with hordes of people over the following weeks who claimed they had contracted diseases of all sorts from swimming at Sydney beaches. Both the Herald and the Telegraph ran stories on problems associated with raw sewage being discharged through stormwater drains in unsewered areas and when the Board's sewers overflowed in wet weather.

All this was a bit too much for the National Surf Life Saving Association, which threatened on 20 January to withdraw its members from Sydney beaches and thereby effectively close them. This was particularly significant because the National Surf Life Saving Association was known or its conservatism. The New South Wales Surf Life Saving Association had been unable to take action because of its dependence on State funding. Action was thought necessary because the Association was concerned that its members might sue them if they contracted diseases such as hepatitis and meningitis in the surf. A spokesman for the National Association claimed that they were seeing an increase in numbers of club members coming down with serious illnesses.

Volunteers had been accustomed to ear and eye infections for years, but this summer had seen an alarming increase in chest and stomach complaints, particularly gastroenteritis, he said . . .

“It’s hardly fair asking volunteer lifesavers to patrol beaches and enter the surf to carry out rescues or training when they stand a good chance of becoming ill”', said Mr MacCleod. (Telegraph, 21/1/89)

More than a month later, the Municipal Employees’ Union also threatened to withdraw paid beach inspectors and life-savers from the job because of the possible health threat to their members. The union issued a reminder to councils of their legal obligation to protect workers from health hazards. Spokesman Brian Harris said, ‘If the pollution on the beaches has reached the stage where councils can no longer meet those obligations we will be advising our members not to enter the water. Under those circumstances the beaches would obviously have to be closed’ (Sunday Telegraph, 5/3/89).

Cartoon by Jenny Coopes for the Sun Herald.

The Sun-Herald ran a feature on beachside doctors, more than half of whom had reported an increase in ear infections, gastro-enteritis and viral infections. Most linked these problems to beach pollution. Some of them, like Dr Margot Wood at Clovelly, who used to recommend swimming to patients with skin problems and for exercise, now advises patients against swimming at ocean beaches (12/3/89). A month or so later, a group of 80 doctors, led by Manly physician Peter MacDonald, called upon Manly and Warringah Councils to close fifteen northern suburbs beaches until they could be proved safe. ‘As “trustees of public health” the specialists and GPs believed it was time to make a stand’ (Sun-Herald, 16/4/89). Just as the fish stories had affected fish sales, so the beach pollution stories put people off going to the beach and affected the tourist industry. Tourists were still visiting Sydney’s famous beaches ‘but only for quick strolls rather than long days at the beach where they once splurged on ice-creams, hot dogs and souvenirs’ (Herald, 28/1/89). It was claimed that takings from shops and businesses at Manly were down 15 per cent on the year before and some people were threatening legal action.

Cartoon by Greg Smith for the Eastern Herald

Surf reporter John Ellis (2MMM) received such a threat from a Manly businessman who claimed to represent twenty Manly businesses that had been adversely affected by Ellis’ warnings not to swim at Manly. It was argued that Ellis’ warnings did not correlate with Surfline reports that showed a much rosier picture of Manly. Surf reporter Mike Petri (2DAY FM) had also been threatened with legal action because of remarks he had made about the Water Board. It was made clear to Alan Tate that this could happen to. him, too. Kirk Willcox, long time member of STOP, lost his job as surf reporter at 2JJJ at about this time, because the ABC said they could no longer afford surf reports. ‘lt’s ironic,’ Willcox said, ‘that I’ve been thrown of the air at this time – when ocean pollution has finally become a front-page issue. Now I have no avenue to voice my opinion’ (Herald, 26/1/89).

Property sales were also reported to be affected by the pollution publicity. The Sun-Herald reported that beach pollution was driving residents away from the beachside suburbs and that some residents believed that real-estate prices were being affected (16/4/89).

Cartoon by Ron Tandberg for the Sydney Morning Herald.

At the beginning of March, Waverley Council approved the installation of permanent warning signs to be installed at their beaches, subject to legal advice. This was a courageous step, given the long history of local councils suppressing bad publicity because of its possible effect on the popularity of their areas, and on local businesses. But they were reluctantly supported by local organisations such as the Bondi and District Tourism Committee.

Local councils had previously sought a legal opinion about whether a council that put up warning signs but nevertheless allowed the beach to remain open could be sued if a swimmer subsequently contracted a disease. They were told by their solicitors in 1981 that a council would have fulfilled its duty by putting up warning signs unless it was patently clear to the council that ‘the pollution was of such a magnitude and the risk so great that no one should be allowed to swim there’. This time Waverley Council’s legal officer advised that in fact signs should be erected, as part of the Council’s ‘duty of care’, indicating that there was some degree of risk to a bather’s health. He suggested that they could take a similar form to fire risk signs.