by Sharon Beder

first published by Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989

Introduction

Sewers seaward

Toothless watchdog

Toxic fish

Sewer-side surfing

Public relations battle

Events of 1989

Beyond Sydney

Conclusion

Bibliography

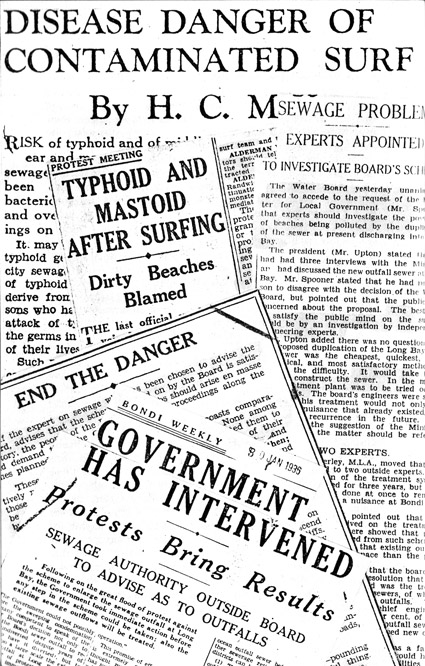

The whole sewage pollution debate really came out into the open in 1936. In that year the Engineer-in-Chief of the Water Board, Farnsworth, proposed relieving the overtaxed Long Bay main by constructing a duplicate ocean outfall sewer, also to discharge at Long Bay. He claimed the location of the new outfall was ‘a matter to be decided upon economic and technica1 grounds only’. This proposal was immediately followed by an outcry. The threat of a worsening situation and the chance that that the Water Board could be coerced into taking action over-came to reluctance of local people to admit to their pollution problems. The Bondi Weekly proclaimed on 30 January 1936: ‘To continue emptying this vile-appearing, foul-smelling abomination just over the coastline of densely-populated districts is an atrocity on the part of those responsible and a reflection on those who tamely submit to it.’

The Telegraph also reported that ‘seaside councils are up in arms, surfers are more than a little perturbed, and seaside property-owners are thinking gloomily of reduced land values’ (17/1/36). The Surf Life-Saving Associations registered their protest and organised protest meetings. And, rather belatedly, the North Bondi Progress Association joined in. Unaffiliated young people canvassed the Eastern Suburbs to ensure a ‘packed house’ for a public protest meeting. The meeting, organised by Randwick Council, was held on 20 January and was ‘largely attended’, attracting Mayors, aldermen and representatives of surf and swimming clubs. It carried a resolution against a sewerage programme that included the use of outfalls such as the proposed one at Long Bay. The resolution suggested that sewerage should be a ‘truly national project’ and recommended that overseas experts be obtained to ‘put into operation modern treatment systems’.

A second meeting was organised by Waverley Council and held on 17 February. The meeting of Bondi residents and representatives of both sides of politics decided to request the State government to ‘insist upon the discontinuance of the discharge of sewage into the ocean near surfing beaches’. There was a protest at the meeting from an alderman that publicity would adversely affect the popularity of the beaches but the Mayor of Waverley replied that the councils had ‘hushed up the matter’ for years and now realised that publicity would achieve more.

Some of the members of the Board were fairly dismissive of public opinion, however. One Board member was reported to have said that the calls for cleaner beaches should be disregarded because ‘the trouble with Australians is that they have a hygiene complex’ (Telegraph, 17/1/36). The Board argued that it had tried alternatives to ocean disposal, such as sewage farming: and they had all failed. In the midst of the outcry over ocean disposal of sewage the Board unanimously adopted the following resolution: ‘that the Board record its adherence to the principle of disposing of sewerage [sic] by direct discharge to the ocean where the cost of so doing is not excessive’ (Board minutes, 8/1/36).

A second resolution, to duplicate the Long Bay sewer, was not supported by the Water Board member representing the Eastern Suburbs but it was attractive to the other members of the Board because it was a cheap, simple scheme, which would allow repairs to be carried out on the existing sewer and would also enable funds to be more quickly allocated to work on unsewered districts, which some of them represented. Support for the Water Board scheme also came from Members of Parliament who argued that priority should be placed on unsewered districts and that occasional beach disfigurement was a lesser consideration. But the support of those voters in unsewered districts was not enough to overcome the massive public outcry over beach pollution. The government insisted that the Board bring in independent experts to review their proposals. The Board agreed that the ‘best way to satisfy the public mind’ was to seek independent opinions.

The choice of ‘independent’ experts was decided by the Board ‘in committee’. Messrs Dare and Gibson were decided upon. H. H. Dare, far from being independent, had acted as a consultant to the Water Board on several previous occasions. A. J. Gibson was a consultant engineer from the firm Julius Poole & Gibson. Dare and Gibson reported a few months later. They reaffirmed the belief of most engineers that disposal of sewage by dilution to sea was the most economical and satisfactory solution in coastal cities. They therefore recommended that the duplicate sewer discharging at Long Bay be built.

They rejected the concept of sewage farming as being too expensive, full of engineering difficulties and ‘a retrograde step’. It would also be too expensive and quite impracticable to divert the existing outfalls elsewhere. Any extension of the outfalls further out to sea would not only be too expensive and difficult but would serve little purpose, since the offensive matter would still come back on shore. Dare & Gibson, unlike the Board's engineers, admitted that sewage would travel in the direction of the wind rather than with the southerly current and that outfalls might cause pollution but they denied that such pollution posed any health threat. The denial of health risks by the authorities was in part their solution for dealing with a situation in which difficult political choices had to be made. Which is more important, Farnsworth asked, the public health advantages of extending the sewerage system or the public health detriment of making the beaches unpleasant for bathing? Ratepayers were not given the choice of paying for both. The complaints that always followed rate increases were taken to speak for themselves. Ratepayers were not told that the price of keeping their rates down was an additional health threat to bathers.

The savings made by disposing of untreated sewage into the sea allowed more money to be spent sewering new suburbs without raising rates. Beachside suburbs tended to be older, working class areas whilst the newer suburbs were expanding to the west, north and south. The large backlog in sewering of new suburbs meant that the priority placed on sewage collection and removal remained even in 1936. Disposal was considered to be far less important. Although the beaches provided a key recreational facility to a1l Sydneysiders, the residents of seaside suburbs had a minority voice. People naturally placed their homes and neighbourhoods ahead of recreational amenities. Beach pollution could be denied, but a lack of sewerage provision was a more obvious health risk and had more srrious political consequences.

Although the decision to cut corners on sewage disposal was a political and economic one, the Board and other government authorities felt that they had to justify the decision. The claim that there vas no health risk was the main justification, but there was also some attempt to portray ocean disposal as a scientific concept. Dilution, oxidation, filtration, oscillation of waves and sterilisation by sunlight were cited to make the ocean disposal seem like sewage treatment. Dare and Gibson claimed that it was ‘not only the cheapest in first cost in most cases, but is just as well established as a truly scientific process as the most elaborate artificial treatment.’ However, they did admit that the tendency, in the United States at least, was towards treatment before discharge. They therefore recommended some very rudimentary treatment in the form of screening and skimming, and suggested provision be made for progressive extension of the treatment process.

The promise of treatment at the outfalls was in the end necessary to quieten the unrest. Although there were still some dissenters, the faith that most people had in the ability of science and technology to provide the answers won the day. The WaterBoard promise of treatment at the outfalls and the findings of the ‘independent’ experts caused media interest and general public concern to recede. The president of the Australian Surf Life-Saving Association accepted the expert opinion, and set about restoring the reputation of Australian beaches. Water Board members congratulated themselves that such eminent engineers had completely endorsed their scheme. The duplicate Outfall at Long Bay (Malabar) went ahead after its endorsement by the ‘independent’ experts in 1936. These experts recommended treatment which was partly installed at Malabar' in the 1970s, more than 35 years later.