by Sharon Beder

first published by Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989

Introduction

Sewers seaward

Toothless watchdog

Toxic fish

Sewer-side surfing

Public relations battle

Events of 1989

Beyond Sydney

Conclusion

Bibliography

When the newspapers started reporting unnamed doctors blaming ear, nose and throat diseases on bathing in polluted waters, this connection was also denied by the authorities. One doctor, referred to only as a well-known eye specialist, wrote in 1936 that the water had been so filthy ‘as to make bathing a questionable performance’ and that contaminated surf water had ‘a very bad effect on the eyes, ears, and mucous membrane (Telegraph, 18/2/36). There were also personal testimonies from surfers who claimed to have suffered septic throats and blood poisoning from the polluted waters. Protesters claimed that typhoid, mastoid growths, ear infections and ‘terrible diseases’ could be caught in the surf. Parliament was told by one MP that it was well known that a number of citizens suffered slight disabilities, such as skin troubles, ‘as the result of going into the surf’ (31/10/28). The Evening News charged: ‘Apparently the health of the thousands of people who visit the beaches to surf is not valued by the board as highly as the estimated expenditure necessary to carry out the essential alterations’ ( 15/7/27).

To counter these allegations, the metropolitan Medical Officer, Dr J. S. Purdy, claimed that he induced his family and friends to sniff Bondi sea water up their noses as a prophylactic against catarrh after observing that constant surfers did not suffer from influenza. Dr Purdy had bottled his samples of Bondi sea water and called it ‘hypertonic supersaturated sea salt solution’. Dr Purdy was reported a few years later as blaming beach pollution on nightsoil dumping and passing ships and claiming that swimmers caught diseases from one another by using common towels. He was reported as saying that even when the surf was ‘grossly polluted’ it did not imperil health.

The denials of pollution and health threats by government authorities were supported by local councils, businessmen and property owners who were concerned that adverse publicity would drive away potential visitors and residents from an area and depress business activity, regional development and property values. Lobbying for remedies for the pollution was often carried on behind the scenes. Deputations from councils would visit the Water Board and put their case to Board members; correspondence between councils and Board members and Members of Parliament constantly took place. But because the Board knew that they wouldn’t go public because of business interests in the area and so were unlikely to rally public support, they were easily ignored.

During the 1920s Randwick Council had been trying to attract surfers and tourists to Coogee. When members of the Coogee Progress Association gave statements to the press deploring the state of Coogee beach and blaming the sewage for ill-hea1th and a sickening stench, the allegations were denied and decried by the Randwick Council. Later Alderman Dunningham, Member for Coogee and former Mayor of Randwick, admitted that the Randwick Council had hushed up publicity about pollution and for many years had dealt with the issue of Coogee Beach pollution in committee—‘in deference to the interests of business people’.

Bondi residents also showed the same tendency towards hushing up poor publicity. On 6 March 1 929, the Telegraph published a large aerial photograph of Ben Buckler point showing the sewage field curving around the point. The photo was headlined ‘Horrible Sewage-Loaded Sea Washes Bondi Surfers’ and immediately set of a wave of publicity and protest. Members of the Water Board immediately denied that there was a problem, insisting that the current swept the sewage away from the beaches. The President of the Water Board, T. B. Cooper, said the Board would do nothing. He said that development in the Bondi area had occurred since the construction of the outfall.

The Bondi sewer, with other ocean outfalls, was inquired into by a Parliamentary Standing Committee. Subsequently Acts of Parliament were passed authorising the construction of those works, and in due course they were carried out by the constructing authority an behalf of the Government, and then handed over to this Board to administer . . . Consequently the Board proposes to do nothing. I may add, it is Sydney's unalterable system. (Sun, 6/3/29)

The Board unanimously agreed that it did not need to take any action.

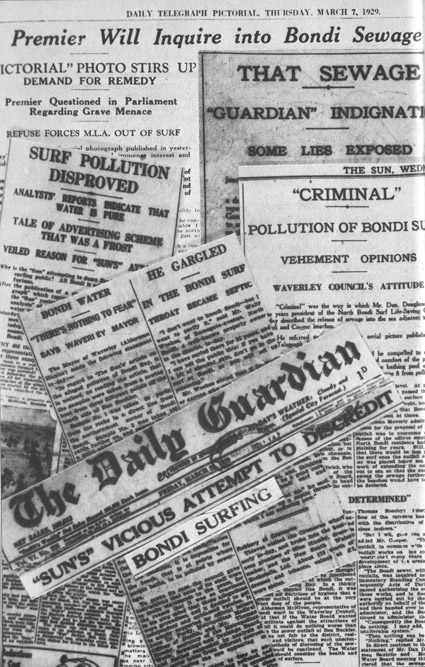

The photograph of the Bondi sewage field published in the Telegraph in 1929 sparked off a public and media debate that lasted for weeks over whether Bondi Beach was polluted or not.

The day after the publication of the damning photo and the Board’s refusal to take any action there was a remarkable reversal in opinion among some people. The President of the North Bondi Surf Life-saving Club, who had earlier described the release of sewage into the sea as ‘criminal’ and had recounted being forced to leave the surf because the beach was littered from one end to the other with ‘offensive matter’, now claimed that the surf was fairly free from sewage and that the stream in the photograph was ‘just an ocean current—not sewage matter’. The Mayor of Waverley, who had earlier called for the removal of the outfall which was ‘against a1l doctrines of hygiene’, now claimed that the photograph showed foam and not sewage and proclaimed the ‘remarkable clearness’ of the Bondi water: ‘It is not fair to the council and rate-payers to say it was an arc of sewage; especially after so much money has been spent to beautify the beach. I do not know of anything more harmful to the district than the publication of that photograph’ (Telegraph, 7/3/29).

In order to settle the question of whether Bondi Beach was polluted the Sun took samples of sea water from Bondi and had them analysed, finding that they contained damning organic matter and that one had ‘bacteria of putrefaction’. Not to be outdone, Purdy and Waverley Council took samples and each found that there was no cause for concern. When the Sun’s samples were challenged they took a further six samples, two of which they claimed were contaminated.

The district, especially the businessmen and Council of Bondi, was said to be up in arms. There were calls to boycott the Sun and Telegraph and withdraw advertising. A ‘monster indignation meeting’ was called against the Sun. The Guardian, a rival paper, claimed: ‘Every citizen of Bondi and Waverley who has his savings in property, or makes his living in a shop, is damaged by this sham “proof” manufactured against Bondi Beach’ (22/3/29). It was later suggested by the Guardian that the photo had been published by the Telegraph because that paper had suffered from the discontinuation of advertising by the Bondi Publicity League. Under the headline ‘“Sun’s” Vicious Attempt to Discredit Bondi Surfing’, the Guardian suggested that there was no real substance to the Sun’s allegations (22/3/29).