Free market environmentalism has two aspects. One is to view the "environment as an asset to be preserved and conserved by private owners rather than considering it a problem to be solved and sustained by government".

The second involves using the market to allocate scarce environmental resources such as wilderness and clean air and replacing legislation with economic instruments where possible. Environmental policy today generally promotes the ‘free’ market as the best way of allocating environmental resources.

The second involves using the market to allocate scarce environmental resources such as wilderness and clean air and replacing legislation with economic instruments where possible. Environmental policy today generally promotes the ‘free’ market as the best way of allocating environmental resources.

Many environmentalists have been persuaded by the rhetoric of free market environmentalism. They have accepted the conservative definition of the problem, that environmental degradation results from a failure of the market to attach a price to environmental goods and services and provide individuals with an incentive to conserve the environment. They have accepted the claim that these instruments will work better than outdated ‘command-and-control’ type regulations.

Far from being a neutral tool, the promotion of market-based instruments is viewed by many of its advocates as a way of resurrecting the role of the market in the face of environmental failure. They claim that economic instruments provide a way that the power of the market can be harnessed to environmental goals. Market-based instruments serve a political purpose in that they reinforce the role of the ‘free market’ at a time when environmentalism most threatens it.

Given the workings of the market in reality, and the well-elaborated imperfections and problems associated with it, what is surprising is that neoclassical economics has not only dominated environmental economics but has also increasingly dominated the whole public discussion of sustainable development.

This influence has manifest in different ways in different countries. In Australia, the infiltration and domination of the Canberra bureaucracy by economic rationalists pushing neoclassical economic solutions influenced the framing of sustainable development policy.

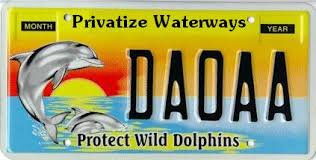

In the United States and Britain, think tanks have been influential. Conservative think tanks in various nations have consistently opposed government regulation and promoted the virtues of a “free” market unconstrained by a burden of red tape. As a result they push for deregulation and privatisation of government provided services and publicly owned resources.

The Washington-based Cato Institute, for example, states that one of its main focuses in the area of natural resources is “dismantling the morass of centralized command-and-control environmental regulation and substituting in its place market-oriented regulatory structures...”

According to Heritage Foundation’s policy analyst, John Shanahan, the free market is a conservation mechanism. In 1993 Shanahan wrote to President-elect Clinton urging him to use markets and property rights “where possible to distribute environmental “goods” efficiently and equitably” rather than legislation arguing that “the longer the list of environmental regulations, the longer the unemployment lines.”

Similarly, John Hood, a visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation and Vice-President of the John Locke Foundation, argued in the Foundation's magazine, Policy Review, that "Corporations pursuing profit have as much chance of generating environmental benefits as regulators or environmental activists do—particularly when they are faced with prices for waste disposal that are as close to cost as possible".

Anderson and Leal from the San Francisco-based think tank, the Pacific Research Institute for Public Policy, juxtapose the market with the political process as a means of allocating environmental resources and argue that the political process is inefficient, that is it doesn’t reach the optimal level of pollution where costs are minimised:

If markets produce “too little” clean water because dischargers do not have to pay for its use, then political solutions are equally likely to produce “too much” clean water because those who enjoy the benefits do not pay the cost... Just as pollution externalities can generate too much dirty air, political externalities can generate too much water storage, clear-cutting, wilderness, or water quality.

Free market environmentalism emphasises the importance of market processes in determining optimal amounts of resource use.

Such thinking has spread throughout the world. Environmentalists have willingly accepted that "all the possible instruments at our disposal should be considered on their merits in achieving our policy objectives, without either ideological or neoclassically-inspired theoretical judgement".

In fact the ideological and political shaping of these instruments has been hidden behind a mask of neutrality. Stavins and Whitehead have argued that "Market-based environmental policies that focus on the means of achieving policy goals are largely neutral with respect to the selected goals and provide cost-effective methods for reaching those goals."

The enrolment of environmentalists has also come about because environmental groups have found it necessity to employ their own economists in order to be heard in an increasingly economics dominated environmental policy arena and they have taken advice from those economists.

Ironically environmentalists who are enrolled in this way are also disempowering themselves. The portrayal of economic instruments as neutral tools removes them from public scrutiny and gives them into the hands of economists and regulators. In fact the decision about levels of pollution, far from being decided in a separate stage of policy making, remains with the polluters since they are given the choice of discharging their pollution or paying the charge or price for a pollution credit. The polluters decide what trade-offs should be made between economics and environmental quality.