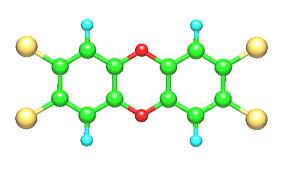

The health and environmental effects of dioxin have been the subject of fierce debate for more than 20 years. Dioxin earned a reputation as “one of the most toxic substances know to humans” as a result of tests on animals which found that one form of dioxin, 2,3,7,8-TCDD, was “the most potent carcinogen ever tested.” There are 75 other dioxin compounds, apart from 2,3,7,8-TCDD, of varying toxicity.

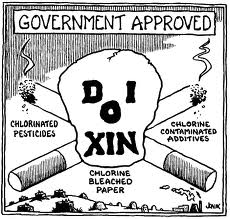

Dioxins are by-products of many industrial processes including waste incineration, chemical manufacturing, chlorine bleaching of pulp and paper, and  smelting. In fact any process in which chlorine and organic matter are brought together at high temperatures can create dioxin. It is for this reason that Greenpeace and other environmental groups have called for phasing out of the chlorine industry.

smelting. In fact any process in which chlorine and organic matter are brought together at high temperatures can create dioxin. It is for this reason that Greenpeace and other environmental groups have called for phasing out of the chlorine industry.

Between the 1950s, when dioxin was discovered to be a contaminant in herbicides, and 1995, when the EPA concluded that the general population may be exposed to unacceptably high levels of dioxins, corporations have set out to confuse the public and influence government regulation of dioxin. They have used corporate front groups, grassroots organising, strategic lawsuits against public participation, conservative think tanks, public relations firms, ‘educational’ materials and the media.

In their introduction to Dying from Dioxin Lois Marie Gibbs and Stephen Lester describe the dioxin story as one that “includes coverups, lies, and deception; data manipulation by corporations and government as well as fraudulent claims and faked studies...It’s a story of money and power; of how corporations influence government actions and how this collusion affects the public.”

One of the key players in this story has been Dow Chemical. It is a major manufacturer of chlorine, producing 40 million tons of chlorine each year, much of which is used to make plastics, solvents, pesticides and other chemicals. In 1965 a Dow researcher warned in an internal company document that dioxin “is extremely toxic” but Dow has always publicly claimed it is not. It is of vital importance to Dow that the dangers of dioxin are minimised and tough regulation of the chlorine industry is avoided. Dow uses lobbying firms and trade associations such as the Chemical Manufacturers Association, the National Association of Manufactures and the US Chamber of Commerce, to influence politicians to vote against increased regulation of the chlorine industry.

One of the key players in this story has been Dow Chemical. It is a major manufacturer of chlorine, producing 40 million tons of chlorine each year, much of which is used to make plastics, solvents, pesticides and other chemicals. In 1965 a Dow researcher warned in an internal company document that dioxin “is extremely toxic” but Dow has always publicly claimed it is not. It is of vital importance to Dow that the dangers of dioxin are minimised and tough regulation of the chlorine industry is avoided. Dow uses lobbying firms and trade associations such as the Chemical Manufacturers Association, the National Association of Manufactures and the US Chamber of Commerce, to influence politicians to vote against increased regulation of the chlorine industry.

Each of these is armed with lawyers and lobbyists who daily stroll the corridors of Congress, the EPA and the White House, influencing public policy in ways unimaginable, and inaccessible, to ordinary citizens. Each of these has a public relations budget, and staff to write op eds, testify before Congress or the EPA, appear on news shows as ‘experts’, speak to civic groups.

Dow Chemical, alone, spent over a million dollars over the last ten years on donations to politicians running for national office and in the 1992 election Dow, together with other chlorine producers, donated more than $1.4 million to people running for Congress. In 1995, Dow provided the services of one of its lobbyists, free of charge, to the House of Representatives Commerce Committee, which has attacked the EPA and environmental protection laws.

Dow executives are given public speaking training so they can take part in various forums as effective and persuasive speakers. In recognition that scientists have more credibility than other company employees, Dow’s “Visible Scientist Program” gives Dow scientists special training to be able to “communicate through talk shows, citizens groups, and newspaper editorial-board briefings about such issues as hazardous-waste management and chemical plant safety.”

Dow also supports and finances corporate front groups such as the Alliance to Keep Americans Working, the Alliance for Responsible CFC Policy, the American Council on Science & Health and Citizens for a Sound Economy. Additionally Dow utilises firms specialising in manufacturing “groundswells of carefully orchestrated ‘citizen’ support for Dow’s point of view.”

In 1985, following a risk assessment, the US EPA classified dioxin as a “probable, highly potent human carcinogen” based on animal data. According to EPA scientists: “When the current data do not resolve the issue, EPA assessments employ the assumption basic to all toxicological evaluation that effects observed in animals may occur in humans and that effects observed at high doses may occur at low doses, albeit to a lesser extent.”

Following the setting of standards in 1985 the EPA came under intense industry pressure to revise them. This pressure was stepped up when, in 1985, dioxin was accidentally found in the discharges from pulp and paper mills that used chlorine for bleaching the paper white. Fish downstream from those mills were also found to be contaminated and tests showed that dioxin was present in the manufactured paper goods. These tests were part of an ongoing study called The National Dioxin Study.

Following the setting of standards in 1985 the EPA came under intense industry pressure to revise them. This pressure was stepped up when, in 1985, dioxin was accidentally found in the discharges from pulp and paper mills that used chlorine for bleaching the paper white. Fish downstream from those mills were also found to be contaminated and tests showed that dioxin was present in the manufactured paper goods. These tests were part of an ongoing study called The National Dioxin Study.

The American Paper Institute set up a ‘crisis management team’ to deal with the situation. Leaked documents, obtained by Greenpeace, show that the administrator of the EPA met with representatives of the pulp and paper industry and promised that the EPA would revise downward its risk assessment of dioxin to ease the problem for the industry. He also agreed to notify the industry as soon as the EPA received any requests for information about the study under the Freedom of  Information Act (FOIA) and that it would not release any results of testing before publication of the final report on the study. The EPA would then send the American Paper Institute a letter saying that testing data was preliminary and meaningless.

Information Act (FOIA) and that it would not release any results of testing before publication of the final report on the study. The EPA would then send the American Paper Institute a letter saying that testing data was preliminary and meaningless.

Attempts by environmental activists Paul Merrell and Carol Van Strum to get results of these tests from the EPA in 1986 through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) were initially fruitless until Greenpeace obtained the leaked documents and Merrell and Van Strum used them in court: “Suddenly the EPA found thousands of pages of documents responsive to our FOIA request that they had previously denied even existed.”

In 1987 the EPA released its National Dioxin Study, following the publication of a Greenpeace report alleging an EPA cover up and collusion between the EPA and the paper industry. By this time the Paper Institute was well prepared with a public relations strategy. It used PR firm Burson-Marsteller to publicise the EPA letter saying the pulp and paper mill data in the report was meaningless. The Institute also advised members approached by the media to behave as if it was “old news” and to “suggest that this is a story that was covered way-back-when...”

I would suggest we use the background statement we already have prepared because it is written in a tone that suggests that what is going on has been going on for a long time. I also would include the article from Scientific American which suggests that dioxin may not be all that serious a health problem....We might not want to include the above material in a formal kit. That might give the appearance we consider this a major event. Instead we might send some material, only when asked, in a regular API envelope.

True to its word, the EPA stated in 1987 that it may have overestimated the risks of dioxin citing the Monsanto and BASF studies as key evidence. A second EPA risk assessment was done in 1988 which suggested that dioxin could be less potent than its 1985 assessment indicated. In the 1985 assessment, it had assumed that dioxin was a complete carcinogen which both initiated genetic change in cells and promoted the proliferation of damaged cells causing cancer. Industry scientists argued that dioxin was only a promoter of cancer and not a complete carcinogen. Among those putting this argument were Syntex scientists. Syntex Agribusiness was responsible for cleaning up a dioxin contaminated town—Times Beach, Missouri—and estimated that “relaxing the cleanup standard from one part per billion (ppb) to ten ppb would reduce cleanup costs by 65 percent.”

Animal studies seemed to indicate that dioxin was a complete carcinogen but it did not behave like either an initiator nor a promoter. Rather than question the initiator-promoter model, which has since been found to be inappropriate to dioxin, the EPA decided to base its risk assessment on a mid-point between the risk of a promoter and that of a complete carcinogen. This would have resulted in the ‘safe’ standard being loosened by 16 times.

However this move was thwarted when evidence of the manipulation of the industry studies was presented to the EPA’s Scientific Assessment Board by an EPA project manager and chemist, Cate Jenkins. The Board subsequently argued that there was no scientific justification for changing the dioxin standards. In the meantime the allegation that the industry studies had been fraudulent was investigated by the EPA’s Office of Criminal Investigations which concluded that this was “immaterial to the regulatory process” and “beyond the statute of limitation.”

When the EPA failed to adjust their standards for dioxin following the 1988 reassessment, the various interests concerned continued to apply pressure to downgrade the standards and to convince the public that dioxin wasn’t really dangerous. A loosening of dioxin standards could mean that pulp and paper mills would not have to install expensive new equipment to reduce or eliminate dioxin being discharged into waterways.

A reappraisal of how dangerous dioxin was could also save dioxin producers billions of dollars in legal claims from those exposed to it. In October 1990 the paper making company Georgia Pacific had lost a court case in Mississippi for alleged dioxin pollution and had $1 million in punitive damages awarded against it. This was expected to trigger many other similar suits against other paper mills in various states, involving thousands of people and worth billions of dollars. Other industries were facing similar legal actions.

In a concerted PR effort between 1990 and 1991 the industry was largely successful in changing dioxin’s public image from being “one of the most toxic substances known” into an innocent victim of scare-mongering environmentalists and overzealous bureaucrats. Vernon Houk of the CDC, speaking at a conference sponsored by Syntex, which was being sued in over 350 dioxin-related lawsuits, argued that EPA standards for dioxin should be relaxed. His statements were influential as he had been the public official who had called for the permanent evacuation of 2000 residents of Times beach, Missouri after dioxin contaminated oil had been sprayed there as a dust suppressant in the 1970s. At the time 75 horses and several cats and dogs had died. Now Houk was saying that those people had been evacuated needlessly:

In summary, with the exception of chloracne... there are no convincing data for the association of dioxin exposure in humans, with early mortality, adverse reproductive outcomes, or chronic diseases of the liver or of the immune, cardiovascular, or neurologic systems. The overall cancer question is not settled, but if dioxin is a human carcinogen, it is, in my view, a weak one that is associated only with high-dose exposures.

Houk was quoted and cited extensively in the media. However when Houk was called before a congressional subcommittee to answer allegations of “improperly aiding the paper industry’s campaign to loosen restrictions on dioxin pollution in water” he admitted that his proposals to relax dioxin standards were “taken practically verbatim from paper industry documents.” This did little damage to his credibility in the media, which had its own links with the paper industry.

The paper industry also set out to cast doubt on the scientific basis of EPA’s dioxin standards. It hired five scientists in 1990 to reexamine a 1978 study showing dioxin caused cancer in mice. This study had been influential and was reputed to have been the real basis for the EPA’s tough line on dioxin. The rat slides from that study were reexamined by the five scientists and tumours recounted. The paper industry’s scientists counted 50% fewer tumours than had been originally counted. Although the new count still showed that dioxin was a more potent carcinogen at low doses than other chemicals, the paper industry used their recount to push the EPA to loosen their dioxin standards.

The Chlorine Institute also attempted to shift the scientific consensus concerning dioxin. In 1990 the Chlorine Institute, a chlorine industry trade group with members such as Dow Chemical, Du Pont, Georgia-Pacific, International Paper, and Exxon Chemical Co, organised a conference of dioxin scientists at the Banbury Center. The Chlorine Institute believed that scientists were coming to perceive that dioxin was not as dangerous as once thought and they hoped that the conference would be “beneficial to our interests, particularly our interest in the paper industry.” It appointed three scientists as organisers and they in turn picked the 38 participants; scientists and regulators from the US and Europe. Also in attendance was George Carlo, consultant to the Institute. The Institute hired Edelman Medical Communications to publicise any conference outcome that was to the Institute’s advantage.

The Chlorine Institute also attempted to shift the scientific consensus concerning dioxin. In 1990 the Chlorine Institute, a chlorine industry trade group with members such as Dow Chemical, Du Pont, Georgia-Pacific, International Paper, and Exxon Chemical Co, organised a conference of dioxin scientists at the Banbury Center. The Chlorine Institute believed that scientists were coming to perceive that dioxin was not as dangerous as once thought and they hoped that the conference would be “beneficial to our interests, particularly our interest in the paper industry.” It appointed three scientists as organisers and they in turn picked the 38 participants; scientists and regulators from the US and Europe. Also in attendance was George Carlo, consultant to the Institute. The Institute hired Edelman Medical Communications to publicise any conference outcome that was to the Institute’s advantage.

Following the conference, Edelman, their PR firm, sent out a press packet with a background paper put together by Carlo, Edelman and the Institute, claiming that the conference had reached a consensus that dioxin was “much less toxic to humans than originally believed.” This outraged some of the scientists present who had not reached this conclusion and who felt that they had been manipulated by the Chlorine Institute.

According to the magazine Chemistry and Industry, the Institute was merely coordinating a “public outreach program” to “capitalise [sic] on the outcome” of the conference. Indeed the industry was able to use the supposed Banbury conference consensus together with the rat tumour re-count to get some states in the US to loosen dioxin standards for discharge of wastes into waterways below those set by the EPA. (They are technically able to do this if they can support their standards scientifically.)

The chlorine and paper industries cited the Banbury conferencein their lobbying of the EPA to reassess its regulation of dioxin. Emerging evidence that dioxin could cause a range of health effects apart from cancer was ignored. The National Chamber Foundation, an affiliate of the US Chamber of Commerce, released a report claiming that “new studies reveal cancer risks from exposure to dioxin are greatly exaggerated” and dioxin “poses no threat to humans, at either normal exposure levels or elevated exposure levels caused by occupational practices or industrial accidents.”

In early 1991 executives from four major paper companies visited the EPA’s director, William Reilly to convince him to reassess dioxin in the light of the new evidence. In a memo following the meeting they thanked Reilly for his receptiveness to their ideas pointing out that their industry was subject to unwarranted “public fears about risk associated with dioxin which bears no relationship to scientific evidence. A consequence of this atmosphere is that our companies are now the subject of groundless class action toxic tort suits seeking billions of dollars in damages.”

According to the EPA’s Cate Jenkins the industry pressure to reassess dioxin represented a “last-ditch effort to win litigation that’s currently pending in the court system”. The assessment would take a few years, during which the industry could win several law suits by arguing that risk from dioxin was low. The paper companies told the EPA: “Reasoned public statements can help calm the needless public alarm that has, in turn, stimulated a proliferation of unjustified legal action against so many companies in our industry.”

Reilly seems to have obliged. The EPA began its third assessment of the risks of dioxin within a few months of the meeting and in August that year William Reilly told The New York Times: “I don’t want to prejudge the issue, but we are seeing new information on dioxin that suggests a lower risk assessment ... should be applied.” This contrasted sharply with the views of many of the EPA’s own scientists. However it was widely reported in the media that the EPA thought that dioxin dangers were exaggerated.

The New York Times, in an editorial, praised the EPA for “sensibly considering new evidence that could lead to relaxation of the current strict and costly regulatory standards” for dioxin and a few days later it ran a front page story beginning “Dioxin, once thought of as the most toxic chemical known, does not deserve that reputation, according to many scientists,” scientists who were not named.

The media generally downplayed the dangers of dioxins during the early 1990s despite emerging evidence that indicated that it was in fact just as dangerous as had previously been thought. Between 1990 and 1993 several studies highlighted that reproductive and immune-system effects of dioxin could in fact be more devastating for human health than the cancer caused by dioxin. One study accidentally found that monkeys exposed to low levels of dioxin every day developed endometriosis and that the severity of the disease increased with increased exposure. Scientists also found that the immune system of mice was suppressed when exposed to relatively low levels of dioxin. “Mice pretreated with dioxin readily die after exposure to a quantity of virus that rarely kills healthy mice.” The amount of dioxin required to cause this affect was far lower than the amount required to cause dioxin’s other affects in animals.