The early Puritans embraced wealth-seeking as compatible with God-fearing and poverty as a sign of godlessness, moral weakness and idleness; “presumptive evidence of wickedness”. The myth of the self-made man also had the corollary that those who were poor were that way because of personal inadequacies, particularly laziness.

The early Puritans embraced wealth-seeking as compatible with God-fearing and poverty as a sign of godlessness, moral weakness and idleness; “presumptive evidence of wickedness”. The myth of the self-made man also had the corollary that those who were poor were that way because of personal inadequacies, particularly laziness.

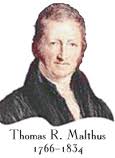

Throughout the 19th Century Christians and businessmen feared the contamination of the working class with morally inferior people. Women were separated from men, and children were separated from their parents, in part as punishment, and in part to protect the children from the bad habits and immorality of their parents. Thomas Malthus (pictured) claimed that the poor laws encouraged vice by providing assistance to the unworthy. An eminent opponent of poor relief, he argued:

of their parents. Thomas Malthus (pictured) claimed that the poor laws encouraged vice by providing assistance to the unworthy. An eminent opponent of poor relief, he argued:

the increasing proportion of the dependent poor, appears to me to be a subject so truly alarming, as in degree to threaten the extinction of all honourable feeling and spirit among the lower ranks of society, and to degrade and depress the condition of a very large and most important part of the community.

Such attitudes to the poor in the UK and the US continued into the 20th century. Writing in 1911 Norman Pearson demonstrated a common view of the poor and unemployed:

It is to be feared that the confirmed loafer and the habitual vagrant are seldom capable of being reformed. It is a mistake to suppose that the typical pauper is merely an ordinary person who has fallen into distress through adverse circumstances. As a rule he is not an ordinary person, but one who is constitutionally a pauper, a pauper in his blood and bones. He is made of inferior material, and therefore cannot be improved up to the level of the ordinary person.