Among the phrases uttered by the talking doll Teen Talk Barbie is “Let’s go shopping!” It sums up the call of today’s toys as they move en-masse down the path of cross-promotion and the celebration of rampant consumerism, leaving questions of children’s development and meaningful play forgotten in their wake.

Many of today’s toys not only entice children to acquire a great many products, they spell out loudly what the products should be. Alongside Teen Talk Barbie can be found a range of Barbies and Barbie accessories which promote and are named after fashion houses, cars and other vehicles, soft drinks and fast foods (see table below for a selection of these). Totally Hair Barbie, the most popular of all Barbies, with over ten million sold, came replete with a tube of Dep hair gel. The Barbie kitchen set has, among its miniature food stocks, Coca Cola and branded biscuits, butter and apple juice.

Many of today’s toys not only entice children to acquire a great many products, they spell out loudly what the products should be. Alongside Teen Talk Barbie can be found a range of Barbies and Barbie accessories which promote and are named after fashion houses, cars and other vehicles, soft drinks and fast foods (see table below for a selection of these). Totally Hair Barbie, the most popular of all Barbies, with over ten million sold, came replete with a tube of Dep hair gel. The Barbie kitchen set has, among its miniature food stocks, Coca Cola and branded biscuits, butter and apple juice.

In many cases, Barbie’s clothes, a prominent part of play with these dolls, incorporate the brand name, logos and other symbols of the promoted product. For instance, the Coca Cola Barbies have the Coke logo emblazoned across their dresses or other costumes, as well as Coke accoutrements. Barbie broadcasts where she and the many products she promotes can be purchased.

In many cases, Barbie’s clothes, a prominent part of play with these dolls, incorporate the brand name, logos and other symbols of the promoted product. For instance, the Coca Cola Barbies have the Coke logo emblazoned across their dresses or other costumes, as well as Coke accoutrements. Barbie broadcasts where she and the many products she promotes can be purchased.

While Barbie has fittingly been dubbed the “patron saint of conspicuous consumption,” she is not the only toy engaged in such promotionalism. The toy car range, Hot Wheels, is immensely popular among boys. In 1998 its two billionth car was produced. It has a range of cars, accessories and playsets promoting Ford, Shell, Walt Disney World, McDonald’s, Mountain Dew soft drink and Nestlé Crunch among others.

From the early 20th Century manufacturers sought to take advantage of parents’ new willingness to splurge on their children and to equate toys with child welfare. Food companies produced toys to promote their products. Campbell’s Soups were among the pioneers, launching Campbell Kids dolls.

From the early 20th Century manufacturers sought to take advantage of parents’ new willingness to splurge on their children and to equate toys with child welfare. Food companies produced toys to promote their products. Campbell’s Soups were among the pioneers, launching Campbell Kids dolls.

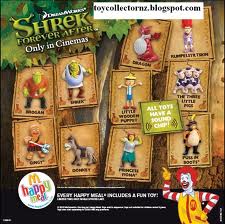

From the 1980s toy makers followed the lead of movie makers, turning their toys into licensing juggernauts. Today movies are based on existing toys such as those based on Bratz dolls and Hasbro’s Transformers in 2007. Re-enactment now features as a central form of play, more commercially lucrative than simply associating the toys with a film or its characters.

Shortly after its venture into Star Wars toys, Kenner collaborated with American Greeting Cards to develop a female character that would lend itself to toy form and  extensive licensing. The result was Strawberry Shortcake, as well as a mass of associated merchandise, a film and a breakfast cereal by General Mills, Kenner’s corporate parent. The doll appeared on every imaginable item from children’s furnishings to toiletries and was given prolific publicity including a hot air balloon advertising her in Britain. The doll grossed $100 million in sales in the US alone during its first year and licensing reaped another $500 million the following year.

extensive licensing. The result was Strawberry Shortcake, as well as a mass of associated merchandise, a film and a breakfast cereal by General Mills, Kenner’s corporate parent. The doll appeared on every imaginable item from children’s furnishings to toiletries and was given prolific publicity including a hot air balloon advertising her in Britain. The doll grossed $100 million in sales in the US alone during its first year and licensing reaped another $500 million the following year.

Kenner immediately followed up with another similar concept for young children, Care Bears, licensed and publicised along  similar lines to the Strawberry Shortcake dolls. The release of Care Bears followed exhaustive research by General Mills and American Greeting Cards to establish what designs, symbols and characteristics would best lend themselves to a range of licensing opportunities. To ensure journalistic enthusiasm, an extravagant expedition was organised, in which journalists were flown to Amsterdam, wined, dined, entertained, accommodated and the following morning taken by coach to an idyllic castle where the complete range of bears and merchandise was presented. After being feted, the journalist from Toys International and the Retailer suggested the toys and other goodies “…are bound to appeal to both children and adults…” In 1993 over nine million Care Bears were sold.

similar lines to the Strawberry Shortcake dolls. The release of Care Bears followed exhaustive research by General Mills and American Greeting Cards to establish what designs, symbols and characteristics would best lend themselves to a range of licensing opportunities. To ensure journalistic enthusiasm, an extravagant expedition was organised, in which journalists were flown to Amsterdam, wined, dined, entertained, accommodated and the following morning taken by coach to an idyllic castle where the complete range of bears and merchandise was presented. After being feted, the journalist from Toys International and the Retailer suggested the toys and other goodies “…are bound to appeal to both children and adults…” In 1993 over nine million Care Bears were sold.

Food manufacturers got on the band wagon, using toys to promote their brands including McDonalds and Burger King. Confectionery manufacturers followed suit, with Hersheys, M & Ms, Reece’s Pieces and Cadbury’s all involved in toys promoting their products. Soon even the multinational corporation Lever Brothers was promoting its Snuggles nappies through dolls, bears and puppets. By 1985 there had been a drastic change in toys and what was being marketed was not a toy but a “concept” around which all manner of merchandise and a string of entertainments could be sold.

The consumerist message in some form is seldom absent from today’s toys, games and children’s entertainment. Toys have taken a highly commodified form which has lent itself to product and brand promotion as well as the promotion of consumerism in general. In today’s marketing-driven global playground merchandise substitutes for open space and exploration. Children’s toys and other areas of children’s play are seen as “cash cows,” there for milking. Marketers emphasise children’s “need” for toys rather than their need for play and they imply that children should amass as many toys as possible.

The consumerist message in some form is seldom absent from today’s toys, games and children’s entertainment. Toys have taken a highly commodified form which has lent itself to product and brand promotion as well as the promotion of consumerism in general. In today’s marketing-driven global playground merchandise substitutes for open space and exploration. Children’s toys and other areas of children’s play are seen as “cash cows,” there for milking. Marketers emphasise children’s “need” for toys rather than their need for play and they imply that children should amass as many toys as possible.

Play is becoming less physical, more computerised and, most significantly, more isolated. According to Philippe Ariès, games and amusements once “formed one of the principal means employed by a society to draw its collective bonds closer, to feel united”. The contrast with modern times is evident. Whereas historically play was a socialising activity, the focus of contemporary toys and games is materialism and individualism.

The idea of children playing alone with their toys, “inconceivable” several centuries ago, is now the basis for much toy marketing. However children today, who have seen advertisements for toys, tend to prefer to play with the toy than with a friend and they tended to prefer to play with a child they didn’t like if the child had a coveted toy than with a child they liked.

Further emphasising the shift from communal to individual play, the design of many contemporary toys suggests that playmates are somewhat superfluous. A toy is represented not only as a plaything but as the embodiment of a friend, and sometimes a needy one. The box of the Baby Chris Gift Set, for instance, claims the doll “needs your love and care,” while advertisements for Pink and Pretty Barbie sentimentalise the doll’s feigned needs: “Pink and Pretty Barbie has everything but the one thing she wants most. A true friend. Will you be Barbie’s friend?” Friendship is reduced to simply another commodity available for purchase at toy supermarkets.

Co-operation should be one of the important social learning areas of children’s game play, with chances for rules to be renegotiated, re-interpreted or improved. If children are isolated and generally play alone with their toys, they are largely deprived of this benefit.

Probably the most commonly expressed concern is that play is becoming much less creative because toys offer less open-ended play opportunities. Whereas toys were once props around which children could use their imaginations and devise any number of play scenarios and play these out, the scenarios, characters and the frameworks for play in modern toys are already spelt out in the movie and television scripts they derive from. This tends to close off other options and provide less scope for the use of imagination. Moreover, if the play is tightly scripted, there will be less room for spontaneous experimentation.

Probably the most commonly expressed concern is that play is becoming much less creative because toys offer less open-ended play opportunities. Whereas toys were once props around which children could use their imaginations and devise any number of play scenarios and play these out, the scenarios, characters and the frameworks for play in modern toys are already spelt out in the movie and television scripts they derive from. This tends to close off other options and provide less scope for the use of imagination. Moreover, if the play is tightly scripted, there will be less room for spontaneous experimentation.

That is not to say that some children won’t still devise their own play but that is not encouraged by the toys and will be the exception rather than the rule. Carlsson-Paige and Levin found, in their study of play, that when play is shaped by commercially-driven and formulaic television programmes toys tend to be over-defined and play is impoverished. Such toys are poles apart from those toys that could be thought of as flexible props and that lead to the sorts of play that gives children a sense of belonging and ownership of their play.

The paucity of play opportunities is often seen in relation to the most blatantly promotional toys. A toy McDonald’s restaurant can be little else and does not encourage children to think of it as anything else when they have seen it so heavily advertised with child actors playing in very specified ways informed by the “McDonald’s experience.” This is ‘brandname’ play rather than developmental play.

The paucity of play opportunities is often seen in relation to the most blatantly promotional toys. A toy McDonald’s restaurant can be little else and does not encourage children to think of it as anything else when they have seen it so heavily advertised with child actors playing in very specified ways informed by the “McDonald’s experience.” This is ‘brandname’ play rather than developmental play.

The same is true of video games which provide little room for children to define their own play. One might argue that children may get some practice in hand-eye co-ordination and in cause-and-effect from these but a multitude of other items could fulfil that role just as well or even better while also providing much richer play experiences.

It suits marketers to have play so well-defined because sharply focussed characters are an effective marketing ploy and scripted play scenarios help to promote individual products as well as consumer culture. The real learning experiences gained from such toys are about consumption, self-gratification and the extent of the dazzling array of commodities on offer. Despite rhetoric of individuality and opportunity that toy makers employ, the major identity offered by their toys is that of conspicuous consumer. Play has effectively been turned into a business and consumed within notions of consumption.