by Sharon Beder

first published by Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 1989

Introduction

Sewers seaward

Toothless watchdog

Toxic fish

Sewer-side surfing

Public relations battle

Events of 1989

Beyond Sydney

Conclusion

Bibliography

STOP began its campaign in early 1985 but soon came up against a public relations effort that would match any in the country. The Water Board hired Silver Partners in mid-1985 to promote the Board and its activities, particularly with regard to its extended outfalls. The Board’s campaign was brilliant, perhaps even too well done. The extended outfalls would, it said, end sewage pollution of the beaches totally and forever. This was the message put across by television and magazine advertisements that were always visually splendid. Pristine beaches and beautiful people evoked a promised future of unpolluted beaches.

The amount being spent on the outfalls was repeated over and over as if just spending this amount of money must guarantee good results: ‘We’re spending millions and there’ll be nothing to show for it.’ The wording of brochures and information booklets was finetuned to give just the right impression. For example, one of the early brochures did not hide the onshore currents well enough. It said that ‘ . . . the effluent/ seawater mixture moves away from the initial dilution zone under the influence of ocean currents. In Sydney, these currents are not normally directed onshore during the summer months’ (Deepwater Submarine Outfalls for Sydney). A reprint of the same brochure was changed to ‘ . . . the effluent/seawater mixture moves away from the initial dilution zone under the influence of strong offshore ocean currents during the summer months’ (Deepwater Submarine Outfalls to Protect Sydney’s Beaches).

The Water Board campaign was also at pains to make the extended outfalls appear to be scientifically sound and technologically sophisticated. The second summer of its new campaign featured advertisements that set out to counter the popular notion that all the outfalls would achieve would be to take be effluent further out to sea from where it would blow back inshore. Several advertisements featured pictures of the diffusers operating.

Ironically, the slick advertising campaign got many people offside. People became suspicious. In a way it contributed to raising people’s awareness of ocean pollution. Each summer, as the Board launched its new offensive, the whole issue of polluted beaches and the question of whether the extended outfalls would solve the problem was rekindled. People wondered why the Board was spending so much money on selling its scheme.

STOP, a small group with no funding, had to rely on media reporting to get attention and had some difficulty getting its views and criticisms published. Powerful organisations with government backing are often able to exert ,considerable pressure on newspapers and journalists, particularly when they think that they are not getting favourable coverage. In such circumstances, journalists need to be convinced of their information and sources if they are critical of these organisations and they also need to be sure of editorial support.

Although some of the papers ran pollution stories each summer they tended to be pitched at a more emotional level. The detailed critiques that STOP was making of Water Board reports were not sensational enough. And STOP people were not accredited experts. Nor were there any readily identifiable experts for STOP to point to. Most medical people, scientists and engineers are not keen to be named by newspapers or to commit themselves in a public dispute.

Newspapers usually need some sort of event upon which to hang their stories so that they are defined as ‘news’. Each story competes for priority and an emphasis on ‘breaking news’ does not encourage any coverage of long-term issues. Not only must the story be newsworthy but it has to attract and hold the attention of readers. Small environmental groups are not usually considered newsworthy unless their claims are judged to be astounding. Some reporters, in fact, try to get activists to make exaggerated and unqualified statements because this is more newsworthy. In contrast, the Water Board was able to centre its press releases around each new stage in be extended ocean outfall development, which could then be classed as news.

Each Water Board press release put forward the case for the extended outfalls. Local papers happily reprinted the releases almost word for word. Every milestone in the construction was marked with pictures of politicians and local dignitaries happily standing over spades with hard hats on. Every article, it seemed, carried the Board's claim that environmental studies had ‘demonstrated conclusively’ that sewage pollution would be eliminated when the new outfalls were completed.

POOO attracted attention once a year with its Annual March Against Pooh at Manly. But no-one wanted to know about the details and the Board’s opponents didn’t have any proof that the sewage was causing any really serious problems. And with- out the details, without the proof, the case for and against depended on presentation, but who could compete with the Water Board's multi-million-dollar budget? The culture of a big newspaper breeds an intensely ambitious atmosphere and few journalists are willing to go beyond the simple, easily understood, easy-to-get story to something that requires analysis and some understanding of scientific or technical issues.

Finally, in May 1986 Peter Dockerill, from the local eastern suburbs paper, reported on STOP’s research under the shock headlines, ‘New Sewer Won’t Work!’ STOP pointed out that a similar treatment plant and extended outfall in Los Angeles had not worked satisfactorily and that Los Angeles City Council was being forced to install secondary treatment before discharge via the extended outfall. STOP also claimed that sewage reaching the surface of the ocean would be blown directly onto the beaches by easterly winds. On the same page the paper had a story about a whale that had been killed in 1934 when it was accidentally hit by a Manly ferry. The whale was towed out to sea several times, as far as twenty kilometres, but it still floated back inshore. Finally it was taken out more than thirty kilometres and was never seen again (Wentworth Courier, 7/5/86). Dockerill also reported Brain’s claims the following week.

The articles in the local papers prompted such concern amongst local residents that the Waverley Council asked its chief engineer to investigate the outfall project and report ‘as to any deleterious effects that might be experienced’. After a meeting with the engineer, three members of STOP were invited to a committee meeting of the Waverley Council to put their case. Most of the councillors were persuaded that there was reason for concern and the council decided to invite representatives of the Board and the SPCC to respond to the matters raised.

The Board and the SPCC sent seven officials to the Council to do battle with STOP and win back the confidence of Waverley Councillors. They took along several display boards and a three-metre-long model of the extended outfalls. As the local paper put it, they flooded the meeting with facts, figures, charts, diagrams and models. They attempted to discredit STOP by labelling their submission as unscientific and an attempt to scare the public. They defended their outfalls, arguing that independent overseas experts had reviewed the Board’s calculations and confirmed their accuracy.

A month or so later the Wentworth Courier said that the Water Board’s public relations team had ‘failed to allay the fears of at least some aldermen’. Waverley Council was left somewhat confused and unable to act. The editorial noted that whilst the Board had criticised STOP’s submission, it had itself appeared to ‘have taken liberties with the truth’ (Wentworth Courier, 10/9/86). The paper referred to an incident at the council meeting when Board representatives claimed that the primary treatment process could remove 60 per cent of the solid matter, implying that this was what was achieved at Sydney’s outfalls. They had been embarrassed and forced to admit this was misleading when STOP member, Kirk Willcox, had put to them that the Bondi plant in fact only removed 11 per cent of suspended solids. (Removal efficiencies are discussed in chapter 4, pp. 75-77.)

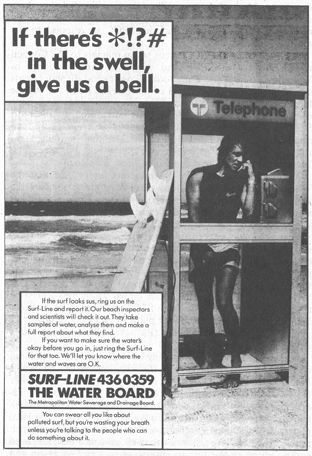

While the surfers were intruding into the engineering domain of reports and meetings, into the very offices of the Water Board and the SPCC with their pesky questions, the Water Board decided to send its own commando force into the surfers’ territory. ‘Surfline’ was established to go out to the beaches and win over the surfers. It was advertised to them in the local papers. One pictured a surfer in a phone box on the beach with the headline ‘If there's *!?# in the swell, give us a bell’ and used surfing idiom in the text to encourage surfers to ring up and report polluted beaches. The Surfline inspectors were ready to come and take samples, get them analysed and ‘make a full report about what they find’.

Surfline was vehemently attacked by opposition politicians such as the Manly State MP, David Hay (Liberal), who described it as ‘nothing but a costly propaganda machine for the NSW Government’. Some surfers also viewed Surfline as a ‘publicity stunt’, according to Kirk Willcox, who was also a surf reporter for 2JJJ and editor of Waves, a surfing magazine. The surfers in POOO argued along with Hay and Water Board Union officials that the money would be better spent on treating the sewage. As Hay pointed out, any surfer could tell when the water would be polluted, from their experience of winds and tides.

Cartoon by Alan Moir for the Sydney Morning Herald.

Under pressure to be seen as honest and independent the Surfline inspectors occasionally reported gross pollution, such as plastic nappies, condoms and plastic bags at Cronulla during the 1986 Australia Day weekend, and slabs of decaying meat at South Curl Curl beach a week or so later. Yet they were still accused of false reporting. At the end of 1986 the Sun newspaper claimed that its reporters had found rats ‘gorging themselves on piles of litter along the water’s edge’ at Maroubra beach while Surfline was reporting the beaches to be clean.

Surfline, with a new no-holds-barred policy, then came into conflict with councils. The manager of Surfline, Leigh Richardson, accused local councils of putting bathers at risk by ignoring Surfline’s advice to close beaches on several occasions. Maroubra beach had been ruled by Surfline unfit for swimming fourteen times between October 1986 and the new year because of high pollution levels and on each occasion Randwick council had refused to close the beach. (The Water Board reported in its Annual Report that all samples at Maroubra for that summer complied with SPCC standards for the geometric mean of faecal coliforms.) The next day the Surfline report warned that there were maggots on the beach and in the water at Maroubra. The Board later stated that the ‘land-based fly maggots’ had been washed down stormwater drains onto the beach but did not pose any health risk.

Cartoon by Greg Smith for the Eastern Herald.

It was reported that the Board had been embarrassed by certain Surfline reports. By mid-January 1987 it was estimated that Surfline had recommended that swimmers not swim or swim at their own risk 62 times that summer. In an article headlined, ‘Has Surfline too much dirt on our polluted beaches?’ the Herald reported rumours that Surfline inspectors were being too honest and had been told to ‘tone it down’ (24/1/87).

There is no reason to suppose that Surfline inspectors were freer than any other Water Board employees when it came to dealing with the media and going against Water Board orders.

Recent revelations about the huge amount of money commanded by the Surfline manager (projected wages and over-time for 1989 of $80 000 – Sunday Telegraph, 7/5/89) suggest that Surfline employees had far more to lose by being disloyal than other employees.

Surfline was also an attempt to restore Water Board credibility, which had sunk to an all time low after years of Board denials of beach pollution. The Herald argued that Surfline’s creation had been ‘an ingenious move by a government department traditionally perceived as secretive and hostile’ (24/1/87). According to the Board’s market research it was a huge success. By 1987 they were finding a 95 per cent awareness and approval rating for Surfline, which was receiving 200-300 calls a day during the week and far more on weekends.

Surfline served the purpose of re-establishing Water Board employees as the experts, the ones who can determine whether or not a particular beach is polluted. Although Surfline inspectors relied mainly on visual indicators for doing this, the Water Board literature and advertisements made much of the sampling and measurements they made and gave them an aura of scientific expertise. They were usually deplicted with clipboards and beakers of liquid, although these containers were assessed visually for turbidity rather than sent to the laboratory for analysis. This downplayed the ability of the ordinary person to judge whether a beach is polluted or not, even though any surfer can do the same.

When the new extended ocean outfalls are built the sewage will be less visible, especially when there is a submerged field. This means that people will not be able to tell whether be beach is polluted just by looking. Much of the rationale for Surfline will be gone. Surfline, which was so successful until the end of 1988, became a target of ridicule when the media began attacking the Water Board early in 1989. Since it was no longer a public relations asset, it was sacrificed in May of that year as people in high places started looking around for scapegoats. Surfline did achieve a number of public relations objectives prior to 1989. One of the most important was to sell the ocean outfalls. By highlighting the pollution, the money being spent on the extended outfalls could be justified. The Board had to tread a fine line between denying that their discharges created gross pollution while still admitting that there was a problem that justified the $450 million dollars the# were spending.

The job of informing the public whether the beaches are clean or not may be turned over to the local councils. Given the long record of local government’s attempts to hide pollution because of the detrimental effect that it has on local businesses, this move is unlikely to assure uniformly honest and open reporting of beach pollution in the future. It seems more likely, though, that the Board will retain control over this task. It will be their best way of ensuring that the new outfalls are portrayed as successful.